The trunk of our white Škoda slammed shut on the last suitcase. Car finally packed. I hopped in. At long last! We were ready to head out on our long-awaited vacation—one thousand kilometers away, on the shores of the Adriatic sea. For a child living in a landlocked country behind the Iron Curtain, it was a dream you dreamed every year. Not least because there were forces that held the power over your ability to travel, to work in your chosen field, to speak your mind in public, and too often, to think.

The drive would be long, that I knew, for we had done it a few times before. It was long because you had to stop at each border crossing, and hope it would all go well. Hope the border guards were in a good mood, that they’d had a good breakfast or at least dinner the night before—and that they’d enjoyed other things that only the adults seemed to know about. Because they would open your suitcases, they would look through the car, and they would ask questions.

Where are you going. Why. How long will you be there. Who are you visiting? You’re not planning on emigrating are you

My baby sister had bronchitis and my father was suffering from eczema, so the doctor had prescribed a few weeks by the seashore for both of them, for the healing properties of the salt water and the fragrant air. The government had graciously, in all of its bureaucratic largesse, approved our request to leave the country, temporarily of course. We weren’t leaving; we were going on a medical vacation. For heaven’s sake, you don’t subject your child to pharmaceutical drugs—you go to the seashore.

Imagine having to petition Congress every time you wanted to travel abroad. For any reason.

We drove through what is now Slovakia—back in the day it was all Czechoslovakia, our country and homeland, forged in the ashes of World War I in October of 1918. If you were Czech, you also spoke or at least understood Slovak, and vice versa (this is why I say I speak 5.5 languages—the 0.5 is Slovak. I don’t speak it but do understand). The two countries were close siblings—the Velvet Divorce, years later, notwithstanding. It never felt like a marriage; it was really a relationship of siblings.

We then crossed the border into Hungary. No trouble there. After all, Hungary was a political cousin. It wasn’t the big bad capitalist West. Somewhere in Hungary, we found a hotel—and pitched a tent in its parking lot. We had to save money for accommodations in Yugoslavia; this was just passing through. One night in a tent we could certainly handle. Plus, my parents had planned: we had camping gear, utensils, a little stove, and canned food. It wasn’t Patagonia or Marmot or Sea to Summit—not even basic by Western standards, but we survived.

“I was so ashamed,” my mom says when I ask her about this part of the journey. “We couldn’t afford the hotel, so we had to sleep in a tent, in the back so no one could see.” Her voice trembles a little.

Today, the trip from my old hometown to the coast of Croatia is a little over a thousand kilometers, and would take approximately 12 hours by car. That’s now. Back then, with the older roads and the long waits at the borders, it took a good two days. Still… if you’ve ever made a cross-country trip here in the U.S., no doubt two days of travel seems trivial. Different, though, when you’re driving a Škoda through the Eastern Europe of the early 1980’s. No GPS, Google Maps, smartphones, or traffic apps. Just good old paper maps, a sense of direction, and street smarts. (Years later I would drive from Rome, Italy, to my hometown, in a rental car and in a single day—no tents necessary. I can’t remember what the speed limits were 😬 —but the borders were a lot more fluid by then.)

The wait at the border between Hungary and the Croatian part of Yugoslavia was a little longer. Okay, considerably longer. We sat in line, waiting for the border officials to “process” the cars driving through. You didn’t question and you didn’t protest. You just sat and waited. Yes, you could get out of your car and stretch your legs. But you didn’t complain. Perfect(ly submissive) behavior, small children included. No hint of resistance or discomfort. I don’t remember a single child crying or complaining during those border controls.

Imagine having to go through a checkpoint just to cross state lines. California to Nevada, say. Or New York to Pennsylvania. Having your car and your bags inspected. And potentially turned back.1

I don’t have a photo of the lines of cars at the border, but the image at the top gives you an idea. (It’s my mom and my sister waiting for the ferry from one of Croatia’s islands back to the mainland. Different context, but same line of traffic. No idea where I am at the time my father took the photo… probably cavorting around nearby.)

Two days after we left our hometown, a glimmer of blue in the horizon. “Moře! Moře!” cried out my baby sister, overcome. “Sea! Sea!” We were in Yugoslavia, the land of warm sand, azure waters, lavender air, and popcorn that tasted of the salt and the air of the Mediterranean. I had brought my white sailor-themed dress and I couldn’t wait to wear it.

The days passed in blissful ignorance of the real purpose of our trip. My baby sister and I played in the sand; I’d carry seawater in my bucket and pour it on the sunbaked feet of vacationers lined up ever so conveniently in a row. I remember being scared of the waves, since I had never seen them before, and so I sat at the water’s edge, mesmerized. Simple things.

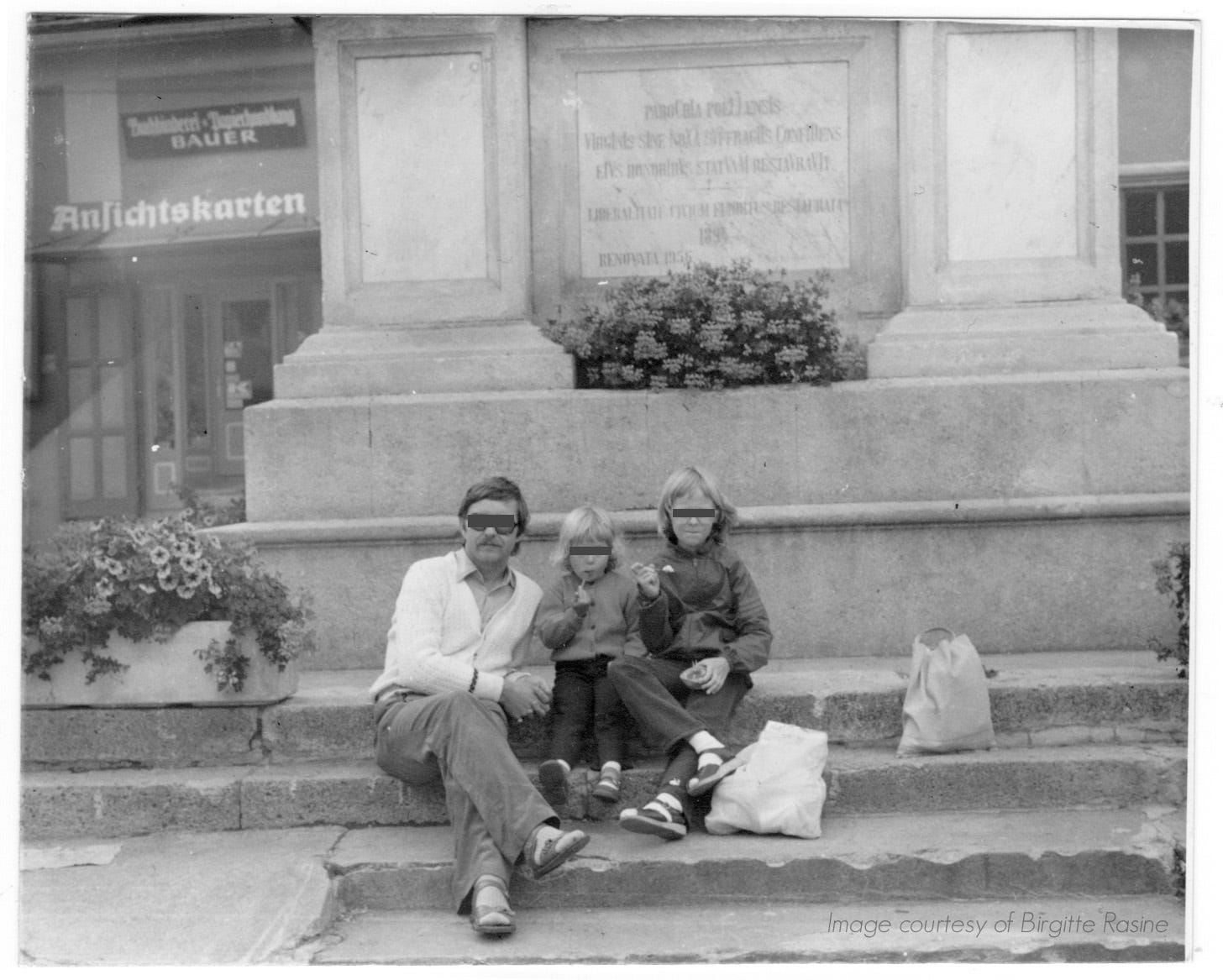

[Above and below] Here we are in one of the old towns of what is now Croatia. That’s me in that oh-so-stylish sailor dress. There is something so timelessly serene about the image below… a mother and her two children. Little do they know the long journey that awaits them…2

One day, as we were all walking down a street, my father said he wanted to tell me something. “Birgitko, we’re not going back home. We’re going to America.”

Then he held his breath. And I let out mine.

“Yeaaay!” I yelled, pumping my little fist in the air. It took a split second for my nine-year-old mind to jump-embrace the thrill and awe of traveling to the land of freedom and wealth, the great United States, and happily wave away all of the attendant nuances of danger and risk. “Jedeme do Ameriky! We’re going to America!” I yelled, jumping up and down.

It was explained to us by the Embassy in Zagreb that Western Europe, apparently, was not accepting refugees from the Eastern bloc. (I know it’s because they were all secretly envious we make better pastries.) So our choices were:

Canada. Too cold.

South Africa. Too far.

Australia. Even farther. But they have koalas.

United States. Ah, just right. Also, what other choice do we have?

Today my father tells me he’d been taken aback by my reaction. He hadn’t been sure what to expect, he says, but he certainly hadn’t expected this level of euphoria. Well, that’s me, Dad! An insatiable world citizen in the making.

If you haven’t lived in an oppressive regime, it’s difficult to express the power that the allure of liberty has. It is stronger than hunger. Stronger than thirst. Stronger than any material comfort or professional ambition. It is the nuclear fuel that powers tens of thousands of people to try to make it to the U.S. and other Western countries every single year. Hold your freedom close.

It didn’t strike me then, as I was still a child. Later, when we were settled in the U.S. and I was a little older, it would all come flooding in. The five overstuffed suitcases. That doctor’s order to visit the seashore. Why the no mention of this “detour” all that time while we were traveling. But there was one thing that really made me mad. I had wanted to take my favorite teddy bear with me on the trip, and my parents insisted I leave it behind. Clearly there wasn’t room for him.

He’d arrive a few years later in the mail, nearly disintegrated after what little baby me had done to him.

My parents breathed, relieved I was onboard. After all, leaving your homeland for an uncertain future with a few suitcases and two young kids is made considerably less convenient if one, or both, of those children determines the endeavor to be less than palatable. Not that we kids had a choice. In the old Eastern bloc countries, you matured politically at a very young age. You knew exactly where your country stood in the line-up of political entities: way in the back, behind an Iron Curtain. You knew better than to make comments in public, be it about the amount of soil on the potatoes in the market, what your friends said among themselves, or heaven forbid any government official. Anyone, even members of your own family, could be secret informants for the Party.

It’s one thing to stop speaking to family members because of your political differences. It’s quite another for a family member to secretly inform on you to the government. That also happened to us—and almost derailed our emigration.

Point of no return

We would never see our apartment again. We would never be able to call home, home, again. The flat would be repossessed by the state—after our extended families had the chance to pick up the things that mattered: our books, our best porcelain and glasses, my sister’s and my toys, journals, clothes, and other personal items. My parents had taken the precaution of not telling a soul—not me, my sister, not even their own parents. One slip-up, and they would have been arrested and very likely jailed.3

As to what would have happened with my sister and me? I’d rather not think about it. The U.S. certainly wasn’t the first one to come up with the idea of separating families seeking a better life outside their home countries.

Imagine being jailed simply for traveling outside the U.S. without the proper government permissions. All you expats and digital nomads would be considered fugitives, and tried and convicted in absentia.

We managed, somehow, to secure passage through Austria. Without that, we would have had zero choice but to return. I’ll spare you the logistical details, for reasons I’m sure you can imagine. We spent a few nights at Traiskirchen, the notorious refugee camp south of Vienna, Austria that would routinely get overrun by desperate people fleeing their home countries. That year was the year of the Poles—political refugees from Poland fleeing uncertainty and lack of work.

There were others, Hungarians and us Czechs mostly. It was my first experience of being technically homeless. There were people everywhere, sitting in the hallways, waiting interminably. The air hung heavy and unclean. The floors of the “bathrooms,” if you can call them so, were marinating in a layer of urine and whatever other bodily fluids had mixed in.

There were no rooms, no privacy. A row of metal bunk beds in a large hall, just enough for a hundred people or so. We were lucky to get one of them. My mom put my sister and me in the top bunk—she wasn’t willing to take a chance putting us within arm’s reach of any of our new neighbors. I remember the darkness of the night there, the din all the people made, and the thin dark blue blanket of a cold, shivering uncertainty that seeped into the marrow of your bones. My mom didn’t sleep a wink that night.

Suddenly “America” felt like a faraway dream.

But we were much more fortunate than many others, who’d spend months in Traiskirchen waiting for passage to the West. Because my sister was still a toddler, we along with a few other families with young children were assigned to a small hotel in a picturesque Austrian village about an hour away.

A little bit of heaven, at least for the children

For my sister and me, the next few months were idyllic. The hotel had a corn field and a pear orchard on the grounds, and lovely mountain trails (imagine what Austria was like in the early 1980’s…). I still remember playing with the other Czech families’ kids in the nearby woods, hidden among the trees and whistling to imitate birds—we knew we got it right because the adults walking past kept looking up into the trees, wondering where the birds were, causing us young songbirds untold joy. And the best part? No school come September! I wouldn’t see a classroom again until that December, when I entered an elementary school in New England.

My parents’ experience, on the other hand, was 5+ months of an emotional state my Mom calls simply… as she puts it, after some thought: displacement. I ask her to describe it a little deeper. “It’s the deep sadness of having to leave your home, your house and everything in it, your whole life, your family, your friends, your work and your colleagues, your country… for an uncertain new life and future. And it’s also this strange kind of nervousness, uncertainty, because you’re not truly sure that everything is ok until you’re on that plane.”

The irony of this has never escaped me.

Pro tip: if you have to flee your country, make sure you’re a little kid under 10. Ideally really adorable. Also make sure you’re not in Latin America or any other country that can’t put you up in picturesque little Austrian towns.4

We were eventually accepted by the United States. This was the news we had been waiting for. Sometime in September, we were called into the American embassy in Vienna to process our travel visas. We arrived with a group of other Czech families. On one of the counters were the passport photos for our group, waiting to be processed. As we sat waiting our turn, two men appeared, stopped by the counter, and picked out a few of the photos. At one point they looked over at us. We heard them speaking Czech.

My mom had a strange feeling about them. Something was off. Why were two Czech men looking through passport photos here at the American Embasy in Vienna? What did become very clear, when it came time to process our visas, is that some of our photos were missing. The Embassy staff couldn’t process the visas and the passports without the photos, and we were sent back to the village, to wait another three months.

To this day we can’t be sure who said what, to whom or where, or what exactly happened, but there is no doubt something untoward had taken place. Our situation became a little precarious. You can never be sure whether a suspicious incident is intended to threaten you, put you in danger, or simply warn you.

Perhaps even more bizarrely, less than two months later we were called in again, and this time the visas were processed without a hitch.

We arrived in New York on a cold and crisp December evening. To my eternal consternation, I slept through the ENTIRE TRANSATLANTIC FLIGHT. What should have been a triumphant, cathartic journey capping months of travel, perseverance, and uncertainty, turned into one long snooze.

I guess we were tired.

I should emphasize that this was a case of legal immigration. As in, we requested political asylum via official channels, because we had managed to get into the physical situation where we could do such a thing. As in, we didn’t have to cross the Sonoran desert or swim the Rio Grande. We didn’t have to risk our lives in a creaky boat trying to motor across the Caribbean to Florida, or from North Africa to Spain or Italy. We weren’t bombed to oblivion on our own land.

Other families certainly faced more risk—a Czech professor our family knew had to swim across a river while border guards were shooting at him (he made it). We heard all kinds of stories of crossing the border, one more unbelievable than the next. Ours was fairly simple, comparatively speaking. It doesn’t leave you clutching pearls (although I really wanted to clutch that teddy bear of mine). But let me leave you with one more anecdote, lest you think we Europeans have always been all about human rights and lovey-dovey mutual support:

On one trip into town when we were in the Austrian village, my mother got to talking with an older local man. “Where are you from?” he asked (in German of course.) “Czechoslovakia,” replied my mother, also in German.

A look of disgust passed over the man’s face. “Oh, you lot should have been killed in the war.”

Shocked, my mother said, “But my great-grandmother was Austrian.”

“Doesn’t matter,” retorted the old man. “They should have killed you all.”

This story was originally meant as an introduction to much deeper discussion about the role and meaning of immigration in this country. It was intended to be a fraction of its length. It was also meant to be published ahead of the election here in the U.S. But something told me to hold off. I didn’t want it to come across as insensitive to the stories of other immigrants—what if Trump wins, and then this falls wrong somehow? When compared to the experiences of the people of Afghanistan, Palestine, Syria, Ukraine, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico… there is simply no comparison. But when the results came in on November 6, I realized I do need to publish it. Because every story of immigration, no matter how smooth or rough, no matter how difficult or happy-ended, matters. And let it be repeated, loud and strong, that each and every one of us here in America, who is not of native or indigenous ancestry, is in fact an immigrant or descended from immigrants. Whether we can continue to say that immigrants make this country great, depends on the choices we allow to be made in the next four years.

If you have an immigration story, I would love to read it. And wouldn’t it be nice to cross-link to each other’s stories…? I sense we might all be surprised at just how nourishing hearing each other’s personal journeys to new lands can be. You can DM me here on Substack or write or link it in the comments.

Most of my posts are free and kept outside iron curtains—I subsidize their exploratory travels so they don’t have to flee my Substack and seek refuge on other platforms. And if you, dear reader, feel so inspired, I won’t ever say no to a little air under my wings:

Or, if the monthly cadence isn’t your cup of hot chocolate, feel free to drop a few coins into the tip jar. Please note… proceeds from this story will help support families in Palestine.

[direct link here if the giphy thingie doesn’t work]

But states are not like countries, you might say, and you would be one hundred percent correct. The comparison focuses on relative size rather than geopolitical entities.

The color photos in this essay are digitized versions of slides. The one black and white photo is an actual print photograph. That’s what we had back then—cameras took only black and white pictures, so if you wanted color images, you had to shoot slides.

The legal threat was real. Article 109 of the penal code of the former Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (CSSR) states, “Whoever leaves the territory of the Republic without permission shall be punished by imprisonment for a term of six months to five years, by reformatory measure or by forfeiture of property.” (Source: Amnesty International, “The Imprisonment of Persons Seeking to Leave a Country or to Return to Their Own Country,” London: Amnesty International, 1986, p.7, via UNHCR)

Apologies for the dark Czech humor.

Glad I had a chance to finally read this. But it also strangely reignites my fury at those who think Ukraine somehow brought the Russian invasion on themselves.

Thank you for sharing that, Birgitte. The part about the teddy bear is a poignant touch. As for the uncertainty your parents had to live through all of those months, I simply cannot imagine.