Ah, AI. You ever-polarizing, profoundly promising, existential-terror-inducing machine angel and devil incarnate. You’ve finally done it. You’ve crossed the Rubicon of human creativity and imagination.

Or so we think.

We stand at a crossroads. It may, in fact, be a cliff. Some of us will sprout wings and chart new flight paths throughout the vast chasm that this fundamental revolution in technology has carved. Some of us will fall to our professional and artistic demise. Some of us will teeter on the edge, thinking it perhaps best to turn around rather than to tempt the Techno Fates—and gravity.

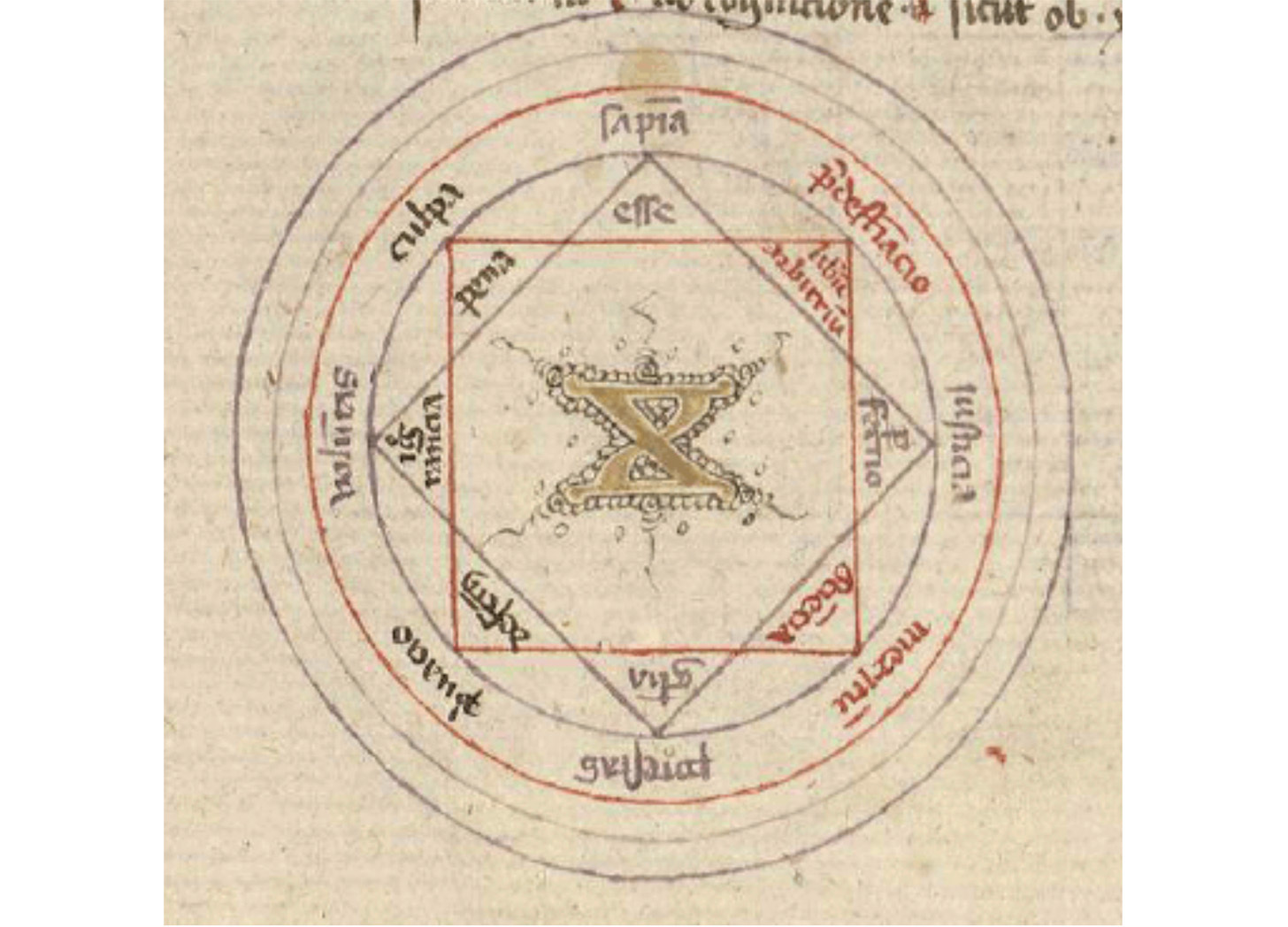

Yet before we travel too far ahead of ourselves, a little background. AI, artificial intelligence, is not a new concept. By most accounts, the term was coined by John McCarthy of Dartmouth College in 1955 in a workshop proposal that effectively established this new field of study. But one of the earliest conceptions of new paths to knowledge formed through mechanical rather than human workings took place way back in 1308 (!!), and it came from Ramón Llull, a philosopher, poet, and theologian from the Kingdom of Mallorca. Llull published the Ars Magna generalis et ultima—that’s Latin for “the ultimate general grand art,” a most humble book title—a philosophical system of universal logic designed for the explicit purpose of proving the truth of Christian doctrine to non-believers.1

I’ll pause there… because when I first read this, I had to take a breath as well.

I know it’s tempting to go running into the night screaming “Religious missionaries invented AI as a tool of mind control!”

Deep breath, maybe two. That’s our animal brain that just ignited. A point of dark irony, yes… but the road from an avid theologian to a network of smart devices and software underpinning virtually every facet of life is a long, unencrypted, and twisting one—and one with no guard rails, frequent mudslides, and plenty of pot holes.

Maybe Llull was first; maybe he wasn’t. Who’s to say Ce Técpatl Mixcoatl, known as the first leader of the Toltecs, didn’t beat him to it in the tenth century by commissioning his priests to devise a system of timekeeping which would glean new knowledge about the heavens? You know how history works. The ones who get written into it are the ones we’re taught to remember.

It does tickle a little to think Llull’s name is a palindrome. I wonder what he thought of that. And if he tucked it somewhere into his magnum opus as a little Easter egg for posterity.

One of my favorite authors, Jonathan Swift, took a parodic swipe at Llull a few centuries later, in 1726, in his brilliant Gulliver’s Travels. (I read this book at age eight—in Czech. I can’t tell you how much better it is in Czech than the original English!) It’s during his visit to the floating island of Laputa that the author is introduced to a strange machine called The Engine, in the town of Lagado (not, as other articles online claim, in Laputa itself. Lagado is the capital of Balnibarbi, a region on the ground beneath Laputa. So, you know, not so much pie-in-the-sky but still pretty out there).

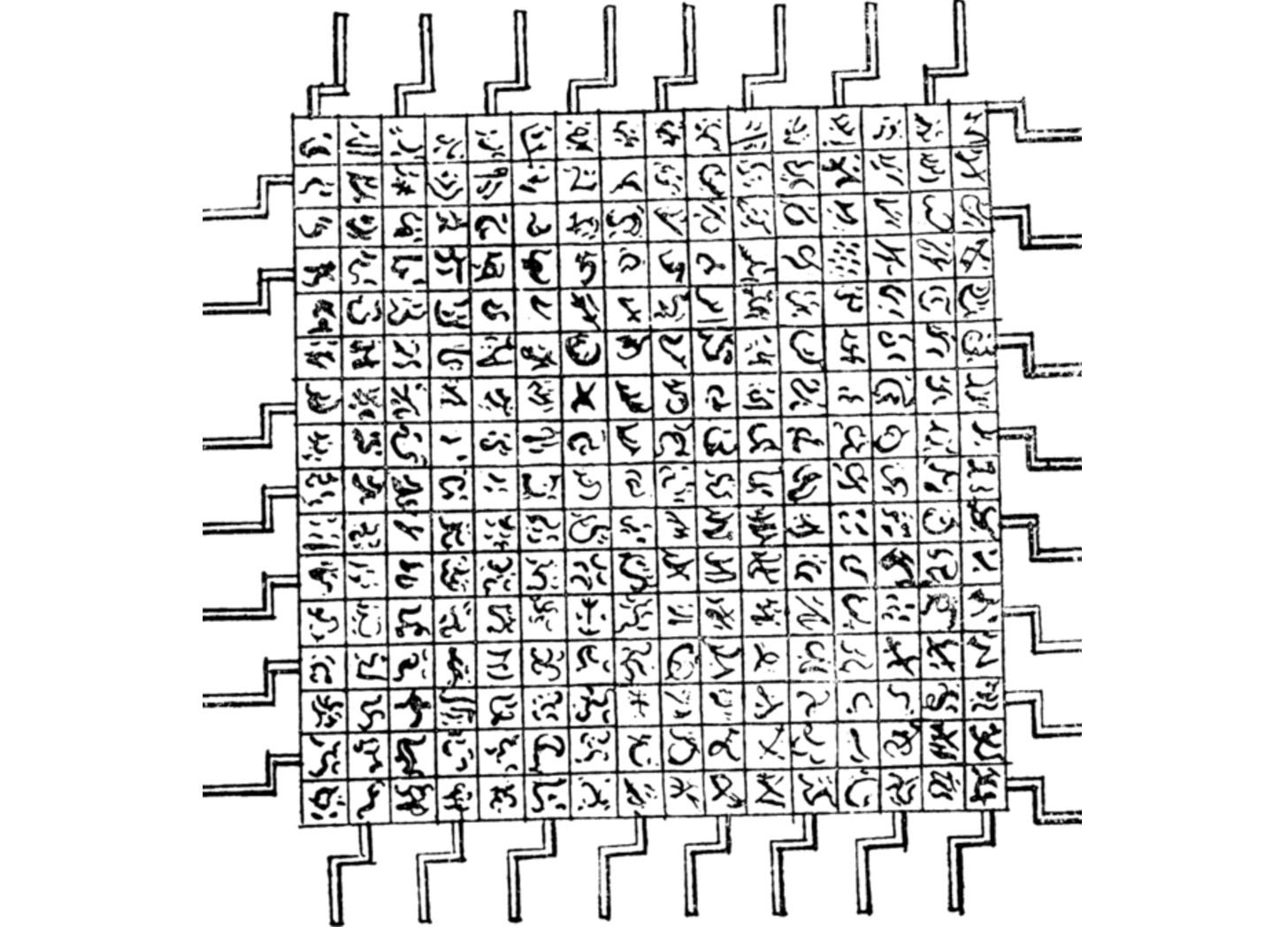

Twenty square feet, The Engine is made of wood, iron, and paper upon which are written all of the words of the Balnibarbian language, and operated by the students of a professor dedicated to “improving speculative knowledge by practical and mechanical operations.”2

How does it work? Why, by pulling the iron handles around the perimeter of the frame, the students would cause the words to change position and configure fragments of sentences. Sure sounds like the precursor of a typewriter to me. At least a fragment of one. That operates in an alternate universe I most passionately do not wish to live in. I should know, I typed my middle school essays on a typewriter. It looked nothing like The Engine but was just as frustrating.

Maybe it’s just me but the drawing above looks like a microchip. I’m sure it’s all just a wild coincidence. Wonder if Jack Kilby and Robert Noyce read Gulliver’s Travels when they were kids…

Some argue it is The Engine, not the Ars magna, that is the earliest written reference to a device that more closely resembles a modern computer. The Engine is a physical device, while the Ars magna presents mere blueprints. Then again, The Engine exists only in the fictional land of Balnibarbi. If nothing else, the term “engine” is certainly more fitting for a computer. But there you have it. A fictitious wooden computer vs theological debate paper templates. If the argument ever wins out, the joke will definitely be on Llull.

(Swift also does a brilliant commentary on the self-absorbed vapidity of the “universal artist” but we’ll save that for another post.)

Whoever lit the first spark that got humanity thinking about thinking machines, it has admittedly been a very, very long road. Just like just about everything else we’ve invented or discovered: electricity, quantum mechanics, nuclear fission, photography, cars, space travel, air flight, the internet, and of course more basic things like the wheel, the compass, and the printing press.

We take for granted a lot of things that make our lives easier, faster, and more comfortable. How often do you appreciate having cold food storage and not having to milk your own cow? Do you feel for those poor miserable peasants of yesteryear who had no Uber to call when warring hordes laid siege to their village? How often do you think about the invisible frequencies that propel your emojis across the country to your friend/sibling/SO/coworker’s smartphone?

You do realize we’d all have been burned as witches just a few centuries ago. Only the witches texted back then, conjured up selfies in the surface reflections of their cauldrons, and flew around on electric brooms.

Do you ever stop and ponder the fact that we’re the first generations in all of human civilization to have lived through this many new inventions and technological changes within the span of a single lifetime? The curve is exponential now, and our heads are spinning so fast we have the illusion of a stationary face staring back at us.

The question is, is that face human.

In Part II, I get to what I had intended to write about before I slid down the rabbit hole of the magical precocious worlds of Llull and Swift: why we anthropomorphize AI.

Disclaimer: No AI was consulted, threatened, hacked, or thrown against the wall in the production of this post.

Cover image credit: Figure X. Ars compendiosa inveniendi veritatem XV Century. Palma, BP, 1031. Digital version Biblioteca Virtual del Patrimonio Bibliográfico. Spain. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. The image appears online at Priani, Ernesto, "Ramon Llull", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.) A great place to start if you’re interested in sliding down the Llull rabbit hole.

You can get your very own copy of the Ars magna generalis et ultima for the basement discount price of US$16,846.98. This is the 1517 edition, not the original, so a little newer, but the cover is still beautifully rotted away.

Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels, (London: Penguin Books, 1985), p. 227.

Some fundamental questions to ask : How does data become Information..?? How does information become knowledge..?? How does knowledge become .. wisdom..?? I stumbled on to these in a course in Creative Teaching. This is Yang stuff.. and I come with the Yin.. only when both combine, we can have understanding and meaning.

Brilliant post, Birgitte. I wrote about Swift's 'computer' myself: https://terryfreedman.substack.com/p/oulipian-omnibus-1 see the section containing the review of The Oulipo and Modern Thought. Such a hoot! Looking forward to part 2.